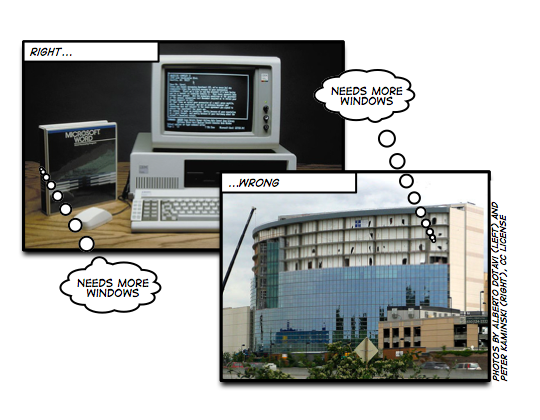

One of the best things about writing a Head First book is that you get feedback from other Head First authors. Our editor, Brett (who you may know from Head First OOA&D), got some interesting feedback from Bert Bates. Bert was going through Head First PMP, and pointed out — and rightly so — that at first glance here seems to be some distance between the PMP approach to projects and the Agile approach.So he’s right. There’s definitely some distance between what you’ll see on the PMP exam and in the PMBOK® Guide, and what you’ll see in an Agile development process like XP, SCRUM, or Crystal. There’s a lot of stuff Agile does that isn’t addressed in the PMBOK, and there’s a lot that’s on the PMP exam that Agile doesn’t address. But this shouldn’t really be a surprise to anyone. See, the PMBOK wasn’t written specifically for developers. A lot of projects that use the PMBOK processes and principles are things that you can’t do iteratively — like, say, highway construction or building a skyscraper. That’s why you see a lot of focus on things like subcontracting and procurement, risk management, communications (which you need to plan for really carefully when you’ve got a thousand people working on a project!), and budgeting. These are things that Agile doesn’t address because they’re just out of its scope.That’s not to say the PMP stuff doesn’t work on software — in fact, it works really well. So why isn’t the opposite true? Why couldn’t an Agile process work for, say, building a high-rise? Jenny and I were lucky enough to have a lot of contact with some of the people who created the PMBOK while we were working on the book. And as it turns out, they were very much into iteration and iterative development. But the PMBOK and the PMP exam need to apply to all kinds of projects, including non-iterative, non-software ones. And iteration does have its place, even in construction. You should definitely approach the design and planning iteratively. But while iteration may work fine for project plans and blueprints, but it doesn’t work particularly well once you’ve broken ground.But there is one big area where Agile and the PMBOK Guide are really similar: managing change. Change management is really important in the processes you need to know for the PMP exam. They are very clear on the fact that changes happen on every project, and that you need to make sure that you plan for change and expect it to happen. Every single knowledge area you need to study stresses that no matter what sort of project you’re working on, you need to constantly look for changes, and make sure that you change course whenever changes are necessary.Sound familiar? It should! Because it’s one of the fundamental goals of Agile development — the Agile manifesto itself says that we’ve come to value “responding to change over following a plan”. And that’s really similar to what the PMBOK tells us: that when there’s a change, we need to modify our plans in order to accommodate that change. (It also wants us to make sure that we know how much the change is going to impact the project, and that everyone involved agrees that the cost of making the change is worth the benefit… which is definitely a good idea too.)

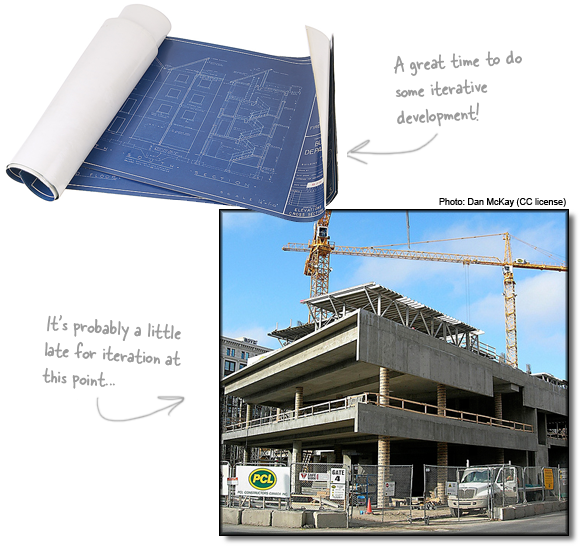

Jenny and I were lucky enough to have a lot of contact with some of the people who created the PMBOK while we were working on the book. And as it turns out, they were very much into iteration and iterative development. But the PMBOK and the PMP exam need to apply to all kinds of projects, including non-iterative, non-software ones. And iteration does have its place, even in construction. You should definitely approach the design and planning iteratively. But while iteration may work fine for project plans and blueprints, but it doesn’t work particularly well once you’ve broken ground.But there is one big area where Agile and the PMBOK Guide are really similar: managing change. Change management is really important in the processes you need to know for the PMP exam. They are very clear on the fact that changes happen on every project, and that you need to make sure that you plan for change and expect it to happen. Every single knowledge area you need to study stresses that no matter what sort of project you’re working on, you need to constantly look for changes, and make sure that you change course whenever changes are necessary.Sound familiar? It should! Because it’s one of the fundamental goals of Agile development — the Agile manifesto itself says that we’ve come to value “responding to change over following a plan”. And that’s really similar to what the PMBOK tells us: that when there’s a change, we need to modify our plans in order to accommodate that change. (It also wants us to make sure that we know how much the change is going to impact the project, and that everyone involved agrees that the cost of making the change is worth the benefit… which is definitely a good idea too.) All in all, I think that there’s a lot of value in the ideas behind the PMBOK and the PMP exam, and that an Agile shop could benefit from understanding and applying them. I definitely don’t think that the PMBOK and Agile development are incompatible. But it’s important to keep in mind that they solve different problems… and that neither Agile nor the PMBOK are intended to be a silver bullet to automatically repair all troubled projects!Oh, one more thing to remember. Jenny and I are software people, and we’ve spent most of our careers trying to figure out how to deliver software projects better. That’s what our first book was about. We spend some time in that book talking about Agile — and a lot of time talking about some specific practices that were popularized along with Agile development: refactoring, test-driven development, continuous integration, pair programming and a few others. We love those practices, and regularly use them on the job. Personally, I always do test-driven development when writing my own code. But that’s definitely an area that you simply don’t see on the PMP exam, and for good reason. What does it even mean to build, say, a highway on-ramp using test-driven development? (Actually, that question may actually turn out to have a meaningful answer. If anyone can think of one, please let us know!)

All in all, I think that there’s a lot of value in the ideas behind the PMBOK and the PMP exam, and that an Agile shop could benefit from understanding and applying them. I definitely don’t think that the PMBOK and Agile development are incompatible. But it’s important to keep in mind that they solve different problems… and that neither Agile nor the PMBOK are intended to be a silver bullet to automatically repair all troubled projects!Oh, one more thing to remember. Jenny and I are software people, and we’ve spent most of our careers trying to figure out how to deliver software projects better. That’s what our first book was about. We spend some time in that book talking about Agile — and a lot of time talking about some specific practices that were popularized along with Agile development: refactoring, test-driven development, continuous integration, pair programming and a few others. We love those practices, and regularly use them on the job. Personally, I always do test-driven development when writing my own code. But that’s definitely an area that you simply don’t see on the PMP exam, and for good reason. What does it even mean to build, say, a highway on-ramp using test-driven development? (Actually, that question may actually turn out to have a meaningful answer. If anyone can think of one, please let us know!)

We’re back!

It’s been a while since you’ve heard from me or Jenny! Did you miss us?

Okay, so first of all, for those of you who were concerned that we might be really bored or something, don’t worry — we’ve been keeping busy. We spent about nine solid months working on our second book. And it paid off — Head First PMP is out on the shelves, and we’ve already got some great feedback about it!

So we’re back. And now that we’re not spending every waking minute working on PMP, we’ve got time to write about all that good stuff you love to read about. Keep your eyes open for new posts. Also, you may notice a slight change in our style. (Once you start writing Head First, it’s hard to stop!) And definitely don’t be shy — you can always get in touch with us on the Head First Labs forum for Head First PMP.

Don’t let uncontrolled changes derail your project

Changes are dangerous. It’s often very easy to loosely describe a change in just a few sentences which, if implemented, would require an enormous effort (and a lot more detailed description). The sales people and product managers still need to figure out what the client needs, but in order to make an informed decision about a change they have to do a real cost-benefit analysis — and that’s where change control comes in. Change control is a process that the project team puts in place to force each change to be evaluated on its actual costs and benefits before the team begins implementing it. A good project manager should watch out for a particularly insidious problem: nobody making decisions about what goes into the project. The buck should stop somewhere — either one person or a team (like a steering committee) should have final say over what goes into the project. It’s easy for people in an organization who should be making decisions to simply look at the project manager and think, “She’s an expert, she knows about the project, so why can’t she decide what goes into the product?” What’s especially problematic about this situation is that, with nobody paying attention to what goes into the software, the team will simply end up gold-plating and the scope will creep.

Luckily, we have tools for handling both problematic changes and scope vacuums. Change control is method for implementing only changes that are worth pursuing, and for preventing unnecessary or overly costly changes from derailing the project. Change control is essentially an agreement between the project team and the managers that are responsible for decision-making on the project to evaluate the impact of a change before implementing it. Many changes that initially sound like good ideas will get thrown out once the true cost of the change is known.

One thing to keep in mind is that each change should be recognized by the team as an explicit change in direction. Someone authorized the project, and the money to pay for it is coming out of a budget somewhere. The person or people who made the decision to fund the project should also be making the decision to extend it. It’s really not within the project team’s rights to take on changes that the stakeholders have already agreed to.