A few days ago I posted an answer to a question about gold plating and scope creep to the Head First PMP forum. I’m not surprised the question came up — people really seem to have trouble with the concept of gold plating. And I don’t think it’s because it’s a tough concept to get. I think it’s because it’s got a lousy name.

In the usual gold plating scenario, a programmer adds features that were never requested because they’re “cool” or fun or seem like they’d be really useful. And sometimes they are — but more often, they’re just wasted effort, at least from the perspective of the person paying the programmer’s salary. Like I pointed out in my last post that mentioned gold plating, I completely sympathize. I’m definitely guilty of gold plating. There was one project I led about ten years ago where I created an entire scripting language, complete with interpreter, that was totally unnecessary. As far as I know, that product is still being used today, and not a single person has ever written one script for it. But it was definitely cool (or, at least, I thought so). More importantly, I really did think it would be useful, and make the software better. Classic gold plating.

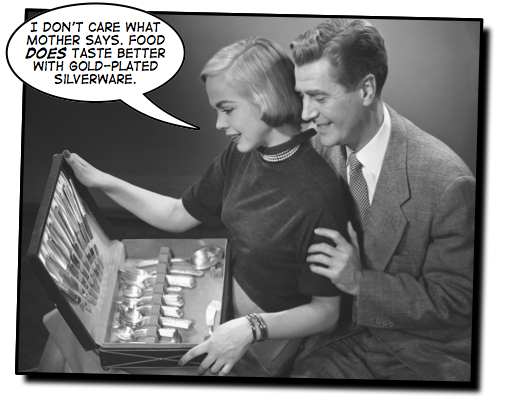

On the surface, the “gold plating” does seem intuitive, but the analogy starts to break down under closer scrutiny. Think about what gets gold plated: all sorts of stuff, from cheap jewelry to expensive pens. All sorts of things get encrusted with, for lack of a better word, bling. And that’s what I pointed out in that forum post:

Gold plating is what we call it when the project team does work on the product to add features that the requirements didn’t call for, and that the stakeholder and customer didn’t ask for and don’t need. It’s called “gold plating” because of the tendency a lot of companies have to make a product more expensive by covering it in gold, without actually making any functional changes. (For example, there are plenty of watches and fountain pens you can buy from luxury companies that are identical to their cheaper versions, except that they’re covered in gold.)

This got me thinking about gold plating, and why it gives people so much trouble. Is gold plating in a software project actually similar to gold plating in real life? Or is it an odd, somewhat mismatched analogy?

To answer that question, we’ll need to take a step back and look at gold plating in the real world. There are a few different strains of gold plating, and they serve different purposes. First there’s the traditional, purely decorative gold plating. That’s the one we know and love: take an ordinary object, slap some gold on it, and charge a whole lot more. That’s the sort of product that’s associated with decadence and conspicuous consumption. It’s where the Gilded Age got its name.

Certainly, making a product arbitrarily more expensive is certainly a way to sell more of it to a certain sort of consumer. But while there are certainly numerous modern examples of opulent gold plating, it’s fallen out of favor somewhat. More importantly, it’s not really a great analogy for gold plating in software.

What it’s been replaced with is a somewhat similar but definitely distinct way to enhance (read: sell “upscale” versions of) products. This “enhancement” is done by adding features that are actually useful, but go far beyond the needs of the typical consumers of the product.

Here’s an example. Hhow many suburban homes really need an industrial refrigerator or restaurant-quality range? Those appliances have been a selling point of “luxury” and “upscale” homes’ kitchens for years. But the difference between that and, say, gilded kitchen items is that the “professional” applicances almost certainly worth the price — if you actually need them. Which you don’t, if you only use your kitchen to cook dinner for four every couple of days and thaw the occasional frozen turkey. But that’s not the point. The kitchen itself has been “upgraded” with cool but unnecessary items. And, in this case, it sells.

That’s certainly not the only example of products packed with features that are potentially useful, but which are, for the average owner of those products, essentially unnecessary (and by and large unused). There’s the slowly fading American love affair with the SUV; the top-of-the-line faucets, fixtures, and general home accouterments that litter the country’s McMansions; and pretty much everything in the Brookstone, Hammacher Schlemmer and Sharper Image catalogs. We’ve got our fill of amateur hill climbers with professional mountaineering gear, weekend golfers with $1,500 titanium clubs, and basement workshops stocked with industrial hardware used to build the occasional birdhouse. Every single one of those things, in the right hands, is almost certainly worth it. I’ve been playing bass guitar for about 20 years, and I know that there’s a big difference between the average $300 instrument and one that cost ten times as much. (Which is not to say you can’t spend $3,000 on a crappy bass, but that’s a whole different issue entirely.) Certainly, a beginner will see some small benefit from using a better instrument. But it’s probably not worth the price for someone who will only pick it up once every few months.

Neither of these two ideas is a perfect analogy for software gold plating. In some ways gold plating in software is a lot like like gilded products. In other ways, it’s similar to the kind of overkill that people perform when they use “top-of-the-line” products unnecessarily. More accurately, it’s really a mixture of the two.

So what drives us to gold plating? We add unrequested (and eventually unused) features because we want to build stuff that’s cool, and it never occurs to us that we’re building something our users won’t need. I like to think of Google as the ultimate in gold plating. Their latest offering, Google Street View, is a great example of cool software that doesn’t seem to meet an obvious need. And I love it — I think they did a great job with it, and I’m honestly impressed with the way a whole lot of moving parts came together the way they did. Maybe someone will think of a really great use for it. But isn’t that a solution in search of a problem, by definition?

A good rule of thumb is that people will generally only pay for a product that’s useful. One of my favorite ways to describe quality is to consider two pieces of software. The first one is beautifully designed, very well built, very stable, never crashes, has a very intuitive user interface, is extremely secure, and is generally a pleasure to use — but it doesn’t do the job you need it to do. The other is terribly built, painful to use, crashes at least once a day, and does 50% of what you need. And that’s the one you’re going to use. It meets your needs. And any feature in that software that doesn’t meet your needs (or the needs of any other users) is pure gold plating.

Which brings me back to the name. I don’t think “gold plating” does justice to the real phenomenon it refers to. It’s more than just gilding software by making it pretty (and/or more expensive). It’s about the way we genuinely feel that we’re making the software better by adding features that may be really cool, but which we, as programmers, simply don’t recognize are useless.

And the sooner we can figure out how to avoid doing that, the better our software will be.

(Luckily, we’ve got some really good tools to help us avoid gold plating. I’ll talk about them soon in another post.)