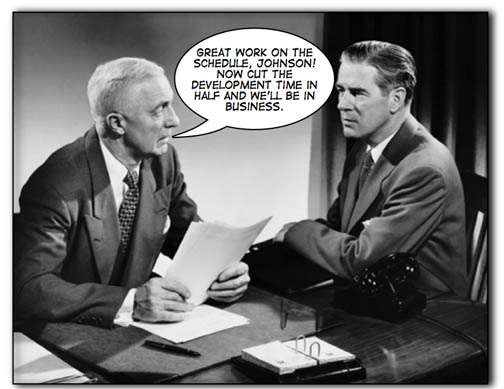

I recently got a question recently asking about Fred Brooks’ famous quote: “Adding manpower to a late software project makes it later.” The person asking the question took it literally, and was asking about whether this meant that there’s no way any schedule estimation technique could indicate that adding manpower could shorten delivery time.

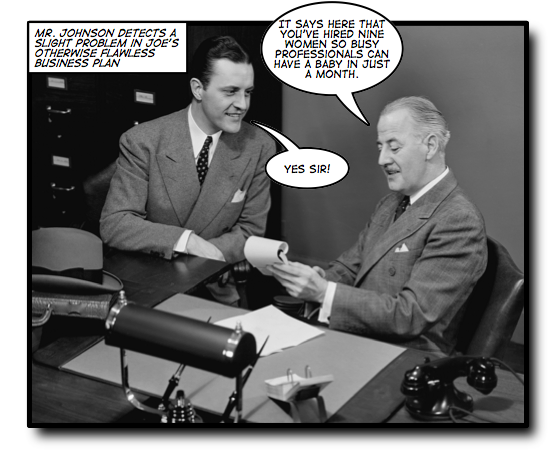

Fred Brooks wasn’t really talking about schedule estimation techniques, or writing hard-and-fast rules. He was trying to help software engineers break some very bad habits. And trying to fix a failing project by throwing bodies at it is one of the worst habits software engineers have. See, as it turns out, some tasks take however long they’re going to take, and throwing bodies at the problem won’t change that. Or, as Brooks wrote, “The bearing of a child takes nine months, no matter how many women are assigned.”

I think the best way to understand that Brooks quote was to understand why he first wrote “The Mythical Man-Month” back in 1975. At the time there was something called the software crisis. The field of software engineering, still young at the time, had run in to a serious problem: people were having a whole lot of trouble writing software on time and under budget.

By the time the software crisis was in full effect, the engineering world had already matured a great deal. The great civil engineering projects of the early 20th century taught us how to manage enormous projects effectively. (Hoover Dam was finished two years ahead of schedule! And Henry Gantt invented of everybody’s favorite scheduling tool around 1910.) And by the mid-1970s, the world of computers had matured to the point where most large corporations had computer programming teams and IBM “big iron” timesharing mainframes. It seemed like the tools were there, and the people had the skills to use them.

So why were all of our software projects so late?

Personally, I blame the person who coined the term “software”. The thinking, I believe, went like this: “Hardware is really expensive, and basically impossible to change. But luckily, we’ve got these programs that we can constantly tweak to suit our needs! That’s the opposite of hardware, which can’t be changed.”

By the time the mid-1990s came around, the field of software project management had matured to the point where we knew that change was the biggest factor in late software projects. Changing needs and requirements meant pulling apart the underpinnings of our code and caused us to have to do expensive (and often ineffective rework). Changing technology kept giving programmers “silver bullets” that they thought would make this next project run a whole lot more smoothly than the last one. And the (perceived) ability to change the software architecture and design in the middle of the project caused a lot of teams to fail to plan their projects well (or at all!).

The worst part of it was that it seemed like the software crisis never ended — there were still an enormous number of projects that were still coming in very late and over budget, or failing to complete at all. But at least by that point we knew the root cause of the problem and had tools to help us fix it. In fact, we were learning that adapting to change and getting those changes under control was an important part of effective software projects.

So how did we know that those things were causing the crisis in the first place, and that fixing those problems would get our software out the door on time and within budget? We can thank Fred Brooks for that. “The Mythical Man-Month” was, as far as I know, the most important software engineering book of its time. It laid out the real problems that caused software projects to run into trouble, and showed us a lot of very useful ideas about planning our software projects, structuring our teams, estimating the work, communicating with each other and our stakeholders, and writing our documentation. And a lot of what he wrote still resonates very well with modern software projects. (A lot of the tools and techniques that Jennifer Greene and I wrote about in Applied Software Project Management were designed specifically to address those root causes of software project problems.)

And that gets back to Brooks’ quote about adding manpower to a late project. When Brooks talked about a late software project, he was talking about a project that had constantly shifting requirements and needs, poor planning, and communications problems both among the team members and between the team and the stakeholders. In a situation like that, many project managers will panic and just try to throw bodies at the situation. (I’ve seen this many, many times — and so have almost all software engineering professionals.) But those extra people will just cause the bad project plan to become even more inaccurate, and they will compound the already serious communications problems. That, in turn, will cause the team to spend extra effort dealing with those problems. And that extra effort will often be larger than the man-hours that the newly added team member will add to the team.

That’s why Brooks called his book “The Mythical Man-Month”. If you need to get your two-person project done in six months, you can’t just add another person on and magically get it done in four months. Adding a person to a project for a month doesn’t automatically reduce the total effort by one man-month. The effort that one person can contribute to a project varies enormously based on the project circumstances. His “adding manpower” is saying that if the project is already late, then adding an extra person can actually subtract man-months from the project.