As a group, we developers have a project tracking problem: the problem is that we constantly, almost obsessively want to track our projects, and it’s made worse by the fact that it’s so easy to abuse otherwise great tools like JIRA and Bugzilla. Unfortunately, while tracking projects may feel useful and productive, for most teams it’s just busywork – and it can lead to a self-imposed exercise in needless bureaucracy that just wastes our time. But with a few ground rules, you can escape the project tracking trap and use a tracking tool effectively.

Who needs Big Brother?

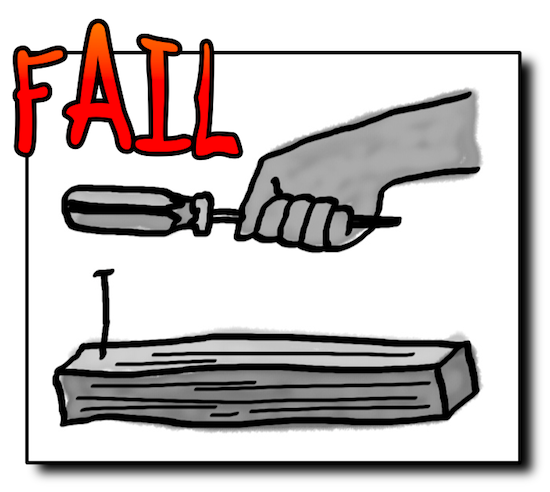

About five years ago, a small company brought me in for a few months to help them do better project management. For about a year before I got there, they’d put a couple of their best developers on the problem, and they came up with an ingenious solution for tracking projects. The team built a database to keep track of all the projects they were working on, typically about a dozen and a half simultaneous projects running at any time. This tool gave them the ability to figure out exactly what tasks had been done, who did them, and how long they took. If you wanted to know what any specific programmer was working on eight weeks ago on Tuesday afternoon, their tool would be able to tell you that.

And it all worked perfectly.

Except that their projects were still late and full of bugs, and the users were losing their last shred of patience. This team had promised their users that things would get better with their fantastic new project tracking system. But even though the system was working exactly as advertised, the software still had serious problems, and everyone was unhappy.

I’ve been thinking a lot about that company lately because I’ve been doing a lot of work with JIRA. And while JIRA is a really good tool – one that can have a very positive effect on how you manage a project – it seems to really tempt a lot of good developers down the same project tracking trap that the small company fell into.

Programmers normally hate it when their time is tracked, which is obvious to anyone who makes the mistake of suggesting to a programming team that they should start filling out timecards that list out exactly what each person did that day. That happened at my first programming job after college: the boss, a newly minted MBA, told the programmers to fill out timecards that listed what project they were working on hour by hour, and there was nearly a rebellion. But for some reason, JIRA, Bugzilla, and other issue tracking systems cause programmers to step up and volunteer for exactly that treatment. It’s an odd phenomenon, and I think it has an interesting explanation.

Let’s get something straight, here: I really like JIRA a lot. It’s a great issue tracking tool, and a very good workflow tool when it’s used right. I’ve spent some time building JIRA plugins, and the plugin API is intuitive and easy to use. Sure, I’ve got a couple of nitpicks here and there (I’m not so happy with the user interface or the filters in version 3.x, although it’s definitely improved in JIRA 4). But for the most part, JIRA is one of the best issue management and workflow tools I’ve ever used.

When it’s used right.

But when you take a perfectly good tool and abuse it, you’re bound to get bad results. And that’s especially true when it comes to project tracking tools.

Tracking projects is not a useful goal

JIRA suffers from a problem that a lot of really good issue tracking tools suffer from. It’s really good at tracking things. And for a lot of developers, that causes a “when you’re holding a hammer, everything looks like a nail†problem. Actually, scratch that. It causes a “you’re holding a screwdriver, but for some reason you want to pound nails with it” problem. It’s odd when you step back from it, but it really seems to make sense at the time.

What happens is that some developers – and I admit that I’ve been guilty of this at least once or twice myself – see a tool that gathers information about what happened on a project, and this causes something to click for us. We  start tracking everything, from requirements to goals to user requests to every little ten-minute task that needs to be done. We become our own “big brother,” doing what amounts to voluntarily filling out the most detailed timecards possible.

The “big brother” style of project tracking is especially bad when the “pointy haired boss†type of managers pick up on it. Suddenly, the team is being nagged to start entering more and more granular estimates and updating dates in tickets. For a boss who’s nervous about delivering something, it seems like the right thing to do is to start nagging programmers about every little task that’s entered into the system, or chasing down anyone who’s got a task assigned without a due date.

Which is especially bad, because that’s not really what those tools are for. There’s a big difference between tracking a task or a bug so it doesn’t slip between the cracks and tracking every little thing that a the programmers do for posterity. I think it’s especially ironic that developers often volunteer for this themselves. I think it’s because we see a tool that can track something and it causes us to want to use it. “It tracks tasks? Then it should track all the tasks!â€

Better living through project tracking

A while back the New York Times ran a story on people who use everyday tools like Foursquare and Twitter, blogs, spreadsheets, and datebooks to obsessively track data about themselves. I think this excerpt is telling, especially the bit at the very end (emphasis mine):

At the center of this personal laboratory is the mobile phone. During the years that personal-data systems were making their rapid technical progress, many people started entering small reports about their lives into a phone. Sharing became the term for the quick post to a social network: a status update to Facebook, a reading list on Goodreads, a location on Dopplr, Web tags to Delicious, songs toLast.fm, your breakfast menu on Twitter. “People got used to sharing,†says David Lammers-Meis, who leads the design work on the fitness-tracking products at Garmin. “The more they want to share, the more they want to have something to share.†Personal data are ideally suited to a social life of sharing. You might not always have something to say, but you always have a number to report.

I think that the sort of person who becomes a developer is especially susceptible to whatever it is that causes some people to obsessively track things about their lives. My personal theory is that this is caused by the same itch causes us to want to obsessively collect every last episode of MST3K (or whatever it is we happen to want to obsessively collect). And like that giant collection of, say, legos or video game cartridges or Start Wars figures memorabilia or dice, at some point we can’t actually play with most of it. That’s fine for collections (assuming you have it in a cool display case, and not strewn all around your home in piles so high that they cause a fire hazard). But for tracking data from projects, it’s worse than useless, because it takes effort to keep up, and it can demoralize the software team because they start to feel like they’re creating more tickets than new lines of code.

Luckily, if you follow a few ground rules, you can break the obsessive cycle and start using project tracking the way it should be used. Here’s what I’ve recommended to people in the past, and it seems to get good results:

- Figure out in advance what you want to track. Most teams use an issue tracker for bugs. A lot of teams use it to figure out what work the developers are going to do. Some use it for new feature requests. I’ve seen people try to use an issue tracker for managing requirements (although personally, I really dislike that use of it). All of that could be fine, but any of it can potentially become obsessive. Before you start your project or the next iteration, sit down with the team for a few minutes and write down what you’ll be tracking. Stick it on a Wiki page, and add a sentence or two explaining how each one of those things needs to be used. I’m always amazed at how just a little bit of planning like this keeps the way we use a tool from creeping into “big brother” territory.

- Use post-mortem reports to track your lessons learned. One reason that “big brother” style project tracking makes intuitive sense is that we want to keep track of the lessons we learned on this project in order to make the next one run better. But there’s very little you can learn from an overwhelming pile of tracking tickets. Instead, try running a project post-mortem at the end of the project. And don’t just do it for projects that ran badly. Post-mortems are really good for making sure you take a good project and turn it into great habits for the team by writing down the lessons you learned.

- Focus on trends and simple metrics, not complete history. A good project tracking system can spit out a lot of reports. So many reports, in fact, that it’s hard to make any real sense of them. That’s why I like to try to simplify the kind of data I get out of the system. I’m a big fan of simple metrics like (% of engineering effort per project phase) that let you compare projects or iterations against each other. Also, burn-down charts or other earned value metrics can be really valuable in figuring out how your current project is going.

The bottom line is that there’s a difference between project tracking and actually managing your project. If you really want to use JIRA for project management, use a tool like Greenhopper that was built for it. (I’ve been using Greenhopper lately, and I like it a lot. But if someone has a pointer to an open source tool they really like that ties a task board or agile project management into their issue tracker, I’d love to hear about it.) The most important thing to remember is that tracking your project is a means to an end, and not a goal by itself.