How do you manage a large project? There’s a big difference between managing a project team with, say, ten people and a team with a hundred. That shouldn’t be too surprising. But if you’re managing your first large project, it can be really daunting. Luckily, there’s been a lot of good work done on understanding large projects and how to manage them. The risks are bigger, and different, than anything you’ve seen on a smaller project. But if you pay attention to the tools that you’re using, you should be able to get a handle on things.

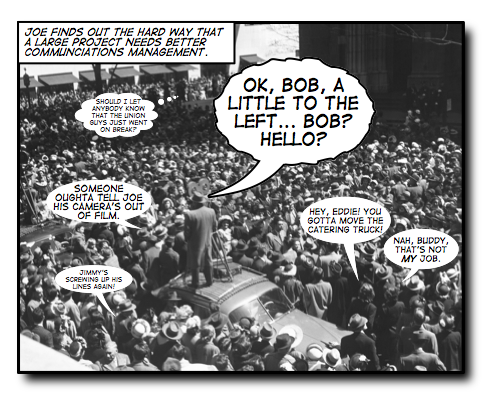

When you’re talking about a large project, communication is the area with the biggest potential risk. That shouldn’t be a surprise; after all, some people say that 90% of project management is communication. The larger your project, the more complex the communications can get.

Anyone who’s studied for the PMP already exam knows about this stuff. Remember that formula you had to memorize for counting lines of communication? Well, this is exactly why you need it! As you add more and more people to the project, the number of potential lines of communication goes up exponentially. And if you’re not prepared for it, you can really lose track of who’s talking to who, and about what. So communications management — putting together a communications plan, keeping your project teams informed, managing your stakeholders’ expectations, and generally serving as a hub of communications — really starts to make a big difference.

Recently, I had to face a situation with increasingly complex communications. I was working with a consulting company that specialized in outsourced software engineering projects. We were assigned a large part of a much larger project, one that was bigger than any other project the client company had taken on. There was another major vendor on the project as well, also doing a large amount of work. In previous projects for this client, we normally didn’t do much work alongside other vendors. But in this case, I saw that the project was divided into several teams on our side, and several more teams in the other vendor’s group. It was clear to me that there would be a large risk of communications problems. So I worked with the project manager from the other vendor to establish communications channels between our leads and theirs (getting buy-in from the client, of course). By planning for and establishing a separate line of communication, we were able to take some early steps to mitigate communications risks. This is definitely paying off now, and the project is going relatively smoothly.

As your project gets bigger, your risk management also becomes a lot more complicated. Which means you need to take more care with how you plan and track your risks. If you don’t already keep a risk register, start. And definitely spend a lot more time talking with your team about risk planning at the beginning of the project. Scott Berkun has a lot of good advice in The Art of Project Management about brainstorming and talking to your team about ideas. All of that good stuff applies to discovering and analyzing risks. Take extra time at the start of the project to work with the team to identify risks, and figure out how to handle them. Are you going to mitigate them? Which ones do you need to accept? Can you figure out ways to transfer the risks? These are all questions you should be able to answer BEFORE the risk materializes. Revisit your risks at regular team meetings. This is one of those areas that really benefits from economies of scale — the more your team is thinking about risk management, the more potential and actual project problems you’ll avoid.

Is your project REALLY large? If you’re managing a project with 1,000 people, then you really need a solid metrics system. You’re never going to get a good handle on what your team is doing by just talking to people — there are simply too many people to talk to! That doesn’t mean you don’t communicate, of course. But you do need to reliably collect data, and then analyze that data statistically. This is what tools like run charts, control charts (or Shewhart charts) and trend analysis were developed for. Here’s a tip: If you’re playing in that arena, and if you have budget for consultants, find yourself someone who’s familiar with those tools to help you set up a system to gather and analyze project data. That sort of thing is very hard to set up once the project wheels are already turning, though, so you’ve got a limited window of opportunity to get it established.

(Inicidentally, if you haven’t read Scott Berkun’s book, you definitely should. I had the pleasure of being a technical reviewer for it, and it’s one of the best books on project management I’ve ever read.)