Well, we didn’t see this coming. Check out what Tim O’Reilly says in his latest blog post:

I was probably most surprised when I saw Programming WCF Services on our list of top performing books for the year. If you’re steeped in open source, you might never have heard of Windows Communications Foundation, Microsoft’s approach to building SOA applications on Windows. And you might not care. But you’d be making a mistake. Don’t count Microsoft out of the Web services game yet! They still have a brilliant, passionate developer community, and as a company have tremendous resources, persistence, and talent. And now that they have real competition, I expect them to reinvent themselves. (For that matter, Head First C# was the top selling programming language title in Bookscan last week, except for “Javascript: The Definitive Guide”. And C# continues to gain significantly on Java in terms of book sales.)

Wait, what? Let me repeat that for you. Except for a book on Javascript, Head First C# was the top selling programming language title in Bookscan last week. That’s pretty amazing to me, because we only released it at the end of November, so word of mouth hasn’t even gotten a chance to spread yet.

We took a few risks with Head First C# — we took an approach that was somewhat different than any other programming book I’ve seen. I’ve learned at least a dozen and a half programming languages over the years, and I followed the same pattern every time: I thought of a project that I wanted to do, then I figured out how to do the project using the new language. (Like back in 1994 or so, when I wanted to learn Perl and also learn about web servers, so I built a web server in Perl.) But I’m definitely not unique in this approach: pretty much every good programmer I know takes the same approach to learning a new language or technology.

Which is why I thought it was so weird that I couldn’t even find a language learning book that asked you to solve programming problems. I’ve seen a lot of “hands-on” work, where you follow step-by-step instructions to type in code to get a certain result. And certainly, an enterprising person can definitely learn that way. (If they couldn’t, nobody would buy programming books!) And certainly, we have a lot of that in Head First C#. But I just don’t think that’s enough.

I guess I have a hidden agenda here. I’ve led a lot of programming teams over the years. In 2006 and 2007, I spent a lot of time working with a consulting company, and one thing you learn working with consulting teams is that you need to work with a lot of different people. Often, you’ll have at least one very junior member on a team. And what I’ve found is that a lot of really junior developers have the capacity to be good programmers, but don’t have any experience independently solving programming projects on our own. So I decided early on that one goal of Head First C# would be to give people that experience. I wanted to teach them how to solve programming problems, rather than just follow step-by-step instructions. In essence, I wanted to create programmers who I’d be happy to have on my team in the future. (Does that sound too self-serving? I hope not!)

So when Jenny and I started working on Head First C#, it took us a few chapters to figure out exactly how to do that. It was interesting going back to the beginning of the book after we finished, to do a second pass and incorporate comments from our (really great, and really patient) tech reviewers. It really did take us about five or six chapters to work out a good way of assigning problems. We ended up co-opting the “Exercise” element that you’ll find in the other Head First books. The Exercises in the other Head First books were generally pencil-and-paper oriented, although I think I remember a few step-by-step programming ones as well. That’s definitely the approach we took in Head First PMP, and it worked really well.

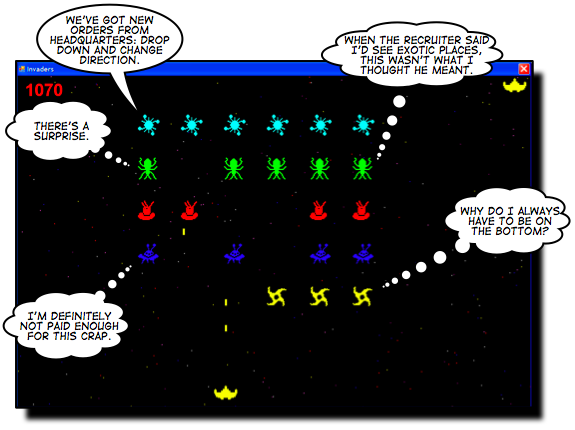

But with Head First C#, we took the “Exercise” element in a totally different direction. We basically used the Exercise to give a programming assignment, where we’d give a problem to solve. We’d include a screenshot, define some classes, maybe give a little of the code, and then leave it up to the reader to build working software. It was lucky that I spent so much of my career writing specifications, because I think we really had to push our writing skills to the limit. It’s far too easy to write an Exercise that’s ambiguous or hard to follow… and as we found out during the tech review, it’s really demoralizing to run across a poorly-written Exercise. And we had to be clear that there’s no single, “correct” solution to the exericse: if it works, then you got it right. I’d be surprised if a single reader comes up with exactly the same solution that we did on any of the projects in the last third of the book.

I hope that interactive approach is what’s paying off. Word of mouth is just starting to get out, and I’m really happy to say that it seems to be positive.