I got a great question from a software developer who also happens to be a fellow CMU alum.

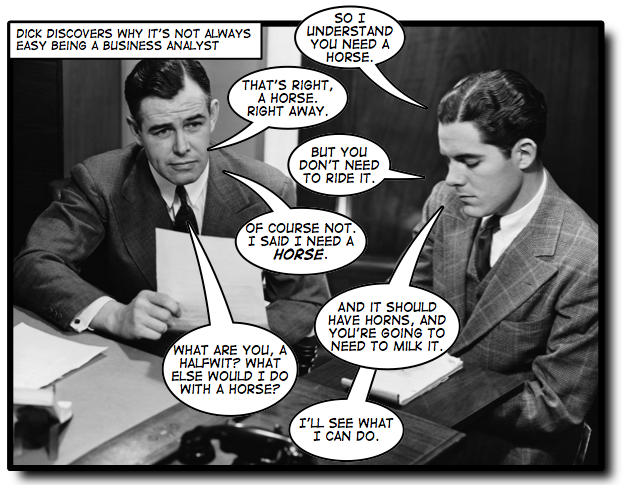

I have a question related to managing scope creep with respect to “on-goingâ€/iterative development processes.

I’m currently managing a project where we’re redesigning my application’s primary workflow. Simply put, the app is currently designed to have users to signoff all items and we’re redesigning it to be exception-based (only require certain items to be signed off).

As we’ve progressed down the path of planned iterative development, a lot of good/new ideas for future enhancements/requirements spring up. I find myself regularly working with my users and “working group†to prioritize and analyze if any of these new ideas need to be considered to build sooner rather than later (and thus triggering plan adjustments or delays).

I often feel like I’ll end up delivering a product that does deliver the initial vision, but still doesn’t make my users happy, as they’ve already shifted their expectations to wanted the “next†thing (aka phase 2).

Do you have any other tips about how to manage this process?

I’ve used things like taking a timeline-style roadmap and adjusting it by overlaying the new requirements and shifting the timeline out. Do you have an recommendations of ways to present this type of information?

Curious your thoughts. Thanks.

— Seth L.

Iterative software development can be a really useful—and highly effective—tool for software development, but it’s also one of the most abused tools I’ve seen. Even as recently as a few days ago, someone in charge of a software team that’s critical to his comapny came to me with the (incorrect) assertion that iteration just means diving into a prototype without talking to anyone or doing any investigation. Iteration done well can lead to very high quality software. But as Seth saw, iteration done poorly can lead to scope creep and serious planning issues.

Making your users “happy†means managing their expectations. They need to see exactly what you’re working on, and what’s coming next. If all people see is deadlines and they don’t have a sense of what’s going on, then they naturally start looking to the next deadline, because that’s all they see. The more visibility you can give them into the way you build software, the more understanding they’ll have – that’s just human nature.

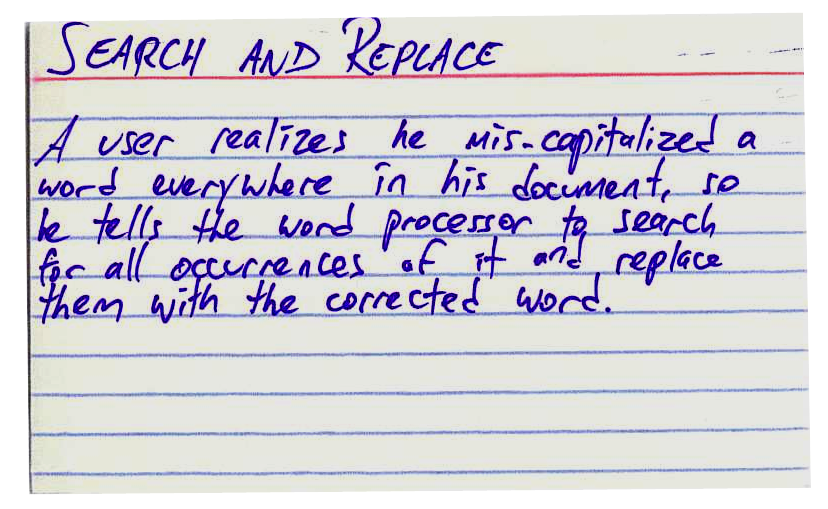

There are a few things that work well for improving visibility into your project’s iterations. One of them is a task board, which typically involves sticking index cards with your user stories or scenarios on a whiteboard or wall. This means that you actually need to have user stories or scenarios. Scope creep is often an indication of a requirements problem, and getting consensus on at least the scenario level about exactly what’s going into the iteration. Having the index cards arrayed on a task board, with each index card showing the status (“planned”, “in development”, “completed”, “out of scope”) gives a lot more visibility into exactly what you’re building and how you’re building it. In a lot of ways, this is a sort of iterative development project plan.

Another way to prevent iteration-related scope problems is committing to delivering releasable code at the end of each iteration. Test-driven development (or, at least, developing complete unit tests) and continuous integration are effective ways to help make that happen. If your stakeholders are comfortable that you’ll deliver high-quality code at each iteration, they’ll feel less pressure to get the new features in immediately, and will be more willing to wait until the next iteration.

If this sounds like something that might help you, I definitely recommend reading the interview Jenny and I did with Mike Cohn for Beautiful Teams, who knows more about agile and iterative planning than pretty much everyone . He has a lot to say about effective iteration planning. There are pictures of task boards he’s used in the past.

That gets me back to the basic idea—one which I give Mike a whole lot of credit for helping people understand—that iterative development, especially in an Agile project, works best when we take the time to plan each iteration. It still faces the same problems: requirements need to be discovered, scope needs to be controlled, and progress needs to be communicated to everyone who cares about it… especially to anyone who can potentially make the developers’ lives more difficult. That’s why the most successful Agile development projects collect requirements and document them using user stories (or other techniques for writing down what the software needs to do). They plan their progress using task boards, forecast them using calculations and charts like project velocity and burn down rates, and constantly keep any business owners and other stakeholders up to date on their progress.

It’s a great way to develop software, and it’s been really effective for a lot of teams. And I think it shows that iterative development does not necessarily mean unplanned development.

When I sent this to the developer who sent me the question, he had an interesting follow-up, which I thought deserved a response:

So I’ve been digesting this a bit and I am curious to get your thoughts about adapting project management fundamentals into the often fluid process of app management. I manage a few virtual projects within my company and at times have struggled to keep things focused as business demands and/or interests shift over time. Similarly, the “iterative†approach has helped to clarify requirements while building out new flows/apps, but as you pointed out can be very tricky to get “rightâ€.

It’s funny how often I hear people say, “Well, this project management stuff works in theory, but my project is fluid†(or “changing,†or “under too much pressure from the business,†or “critical,†etc.). It turns out that pretty much every project is challenging, and project management is set up specifically to deal with that kind of challenging project.

Here are two thoughts I had relating to this idea.

First, the iterative development model works very well, as long as you’re committed to delivering a high-quality product at the end of each iteration. Whether or not you develop using an iterative approach, you need to manage change: prevent unnecessary changes, and make sure you understand the impact of any change that you make. It also means that you need some sort of scope baseline, so that you know what is and is not a change. It’s faster and easier to update software on paper, before it’s written into code, so the more changes you can move to the “write it down and review it†phase of your project, the better.

And second, if your business is overly demanding, it often means that you could manage your stakeholders’ expectations better. Make sure you identify them – and write down their names and needs! – from the very beginning of the project. Talk to them… a lot. Make sure they’re in the loop. If possible, see them so often that they’re sick of seeing you. If they’re always aware of what you’re doing, there won’t be nearly as many surprises. Also, the more your stakeholders understand the details of the work that you’re doing, the more slack they’ll cut you when they ask you for changes. Often, when someone puts a lot of pressure on you to do the impossible, it’s because they don’t realize that’s what they’re asking.