What is it with futuristic kitchens? I swear I’ve seen the same TV segment about the “kitchen of the future” repeated on different channels with different people at least twice a year for the last decade or so.

This wired article seems to have a good description of the generic kitchen of the future:

Kitchen of the future

General Electric

What if your appliances were so smart they took the drudgery out of meal preparation? “Your kitchen can basically be your sous chef,” says Marc Hottenroth, an industrial designer who helped create GE’s concept kitchen. Call home from work and your pantry and fridge – outfitted with RFID readers – will tell you what’s stocked, suggest meal options, and list the ingredients you’ll need to pick up at the grocer. (They’ll also remind you to buy milk when you’re almost out.) Craving a quiche? GE’s kitchen will guide you through assembling one and heat the oven to the optimal temperature. If, say, elderly Aunt Rosa is visiting from Italy and wants to whip up some gnocchi instead, the appliances can display text in larger type … and in Italian. What’s more, GE’s setup redistributes energy (such as using excess oven heat to warm dishwater) to lower power bills. Rather not cook tonight? The kitchen can find a number for pizza delivery.

There you go! It’s got everything. It gives you recipes, tells you what’s in your fridge, and lets you look up phone numbers. All that, and it will remind you to buy milk.

Sounds great! So why does the kitchen of the future rub me the wrong way? And, more importantly, what lessons about building better software can we learn from the kitchen of the future?

Let’s put aside for a moment the fact that it’s pretty unlikely that your elderly Italian aunt Rosa doesn’t already how to make gnocchi. There’s one thing that’s true about every engineered product, whether it’s a stove, software or a slide rule: it’s built to meet someone’s needs. But there’s another thing that’s almost always true: some needs aren’t obvious. And it may just turn out that you’re building a kitchen that doesn’t actually meet real needs that people have.

Here’s an example. A hat seems like a pretty simple product that meets a straightforward need, right? It keeps the sun off your head. But wait a minute… plenty of people wear baseball caps inside, where there’s no sun to protect you from. And they’re not playing baseball. So hats fill another need — they help the wearer feel fashionable. And there are other needs, too. A baseball cap has a visor that’s placed in a way that shields your eyes from the sun, but it also advertises a sports team, and, when adorned with the proper Greek letters and bent in exactly the right way, makes frat boys look cool to other frat boys. Those are all important needs.

What about a toy program that you just threw together in your spare time because you were bored? Does that fill a need? Sure! You needed to kill some time, and it served that need perfectly.

So what does all this have to do with the kitchen of the future?

Take a minute and have a look at this excerpt from a CNN transcript of a segment about one particular kitchen of the future:

TIM WOODS, VICE PRESIDENT, INTERNET HOME ALLIANCE: This is kind of a nerve center for the entire kitchen. In fact, it’s the nerve center for the home. This is the HP TouchSmart PC. And it’s kind of social computing, right, at its best.

But the idea here is, you put everything in one place at a touch point. There’s a middleware program on this from a company called Exceptional Innovation. And what that did is, it brought all of these elements like lighting and shade control and music, and put them all into one interface. Now, mom does about 80 percent of the input on any family calendar, but she wants the ability for dad to go in there, the kids to go in there, leave notes – do all of these things that really become tools for the family.

Now, I don’t want to knock HP and Exceptional Innovation. I’m sure they worked hard on their software, and I certainly know what it’s like having a product to sell. And they’re following the siren call of the Kitchen of the Future that plenty of people have followed before, and I can’ blame them for that.

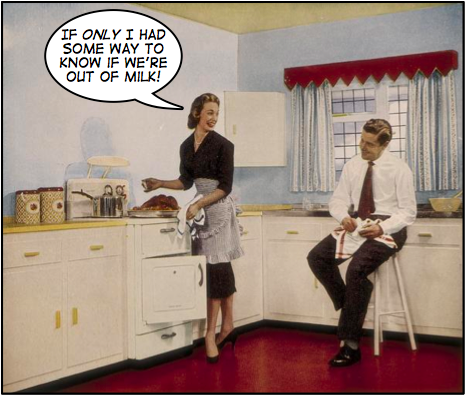

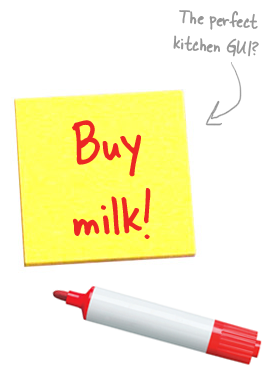

But really? Controlling the lights and keeping a family calendar — is a computer really the best way to do that? Most families have a dry-erase board or calendar stuck to the fridge. It meets their planning needs really well. It’s much more Agile. (And, interestingly, it never crashes.) Think about it from a software development perspective: do you want to go through a whole bunch of screens in a touch-screen GUI to get to your calendar? Or do you just want to go scrawl a note with a marker? Which of those seems “heavyweight”? Which seems more agile?

The same goes for controlling the lights and the entertainment center. Most kitchens have a small handful of lights. I’ve yet to find a software interface that works better than a light switch or a dimmer on the wall. Plus, you can find a light switch in the dark when you’re half-asleep and looking for a midnight snack. I’d be surprised if that’s a need that most lighting control software developers realistically considered.

Which brings me to buying milk. Just about every Kitchen of the Future I’ve seen in the past ten years makes a point of being able to tell you that you’re out of milk. (On the video, the computer in the CNN segment showed an image of a Post-It note displaying a hand-written note that read, “Buy milk!” I have the feeling that showing a picture of a Post-It note seems, from a UI perspective, to be an admission of defeat.) Is it a real need? Yes, with the exception of or vegan friends, we do all need to buy milk.

But is it really so hard to figure out when you’re low on milk?And if it is, can we realistically expect the kitchen to know when we’re low on milk? Will we always need to put the milk on a special Weight sensor? Will I get a false alert when little Kaitlynne or Brandyn puts the milk back on the wrong spot in the fridge? Does it know when my milk’s gone bad, or only if it’s low? It all seems far more complex and error-prone than just having a stack of Post-Its and a marker next to the fridge. The simplest and most convenient solution to the problem is still scrawling “buy milk” on a Post-It and sticking it somewhere obvious.

And that’s my point. When you get down to it, the Kitchen of the Future is available to us today at a reasonable price. Why don’t we all have one? Because it doesn’t meet a need. It’s an Exercise in gold-plating. It’s a solution in search of a problem. And I get it. I’m a programmer at heart, and I love new applications of cool technology significantly more than the next guy. But we won’t find buyers for our products if they don’t fill a need.

And that’s the software lesson to learn here. Make sure your software always meets someone’s needs before you start building it. Because the last thing you want is to put your Kitchen of the Future out there, only to discover that the world’s just not ready for it yet.